Major Challenges to the Major Questions Doctrine

Is the Supreme Court just another disingenuous, hyper-politicized institution?

Imprecise legal reporting and commentary generates much confusion about the state of American jurisprudence. Many observers misunderstand the complex relationships between related doctrines such as the nondelegation doctrine, Chevron deference, and the major questions doctrine.

The major questions doctrine is the legal theory that says that judges ought to presume that Congress did not transfer to the administrative state significant powers unless it did so clearly. It requires the Article II agencies to demonstrate affirmatively that the legislature did in fact delegate the “major” powers they claim. Most prominently, the Supreme Court in 2022 deployed the doctrine to strike down a sweeping — and statutorily dubious — regulation from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) inWest Virginia v. EPA.

Skeptics of today’s Court charge that the major questions doctrine is little more than a slippery legal theory that provides the conservative majority with a convenient means to rationalize ruling for its preexisting policy preferences.

This author responded at The American Spectator:

Legal observers — and the American public — should weigh this charge seriously. While jurists will inevitably disagree in good faith on various matters of law and interpretation, any court that departs deliberately from legislative text and intent exceeds its legitimate constitutional authority and rules arbitrarily as well as illegally. However, (Supreme Court Justice Elena) Kagan’s criticisms fail to grasp that the major questions doctrine (when properly applied) in fact directs judges toward the best, most plausible statutory interpretations — not toward their ideological priors, as Kagan charges.

When applying the major questions doctrine, judges expect Congress to speak clearly if it wishes to invest executive agencies with powers of vast political or economic significance. Concurring in Biden v. Nebraska (2023), in which the majority struck down President Joe Biden’s student-forgiveness gambit, Justice Amy Coney Barrett explained this doctrine’s nexus with faithful textualism. “The major questions doctrine situates text in context, which is how textualists, like all interpreters, approach the task at hand,” Barrett writes. To this she adds, “To strip a word from its context is to strip that word of its meaning.”

Language is plastic. A clever enough mind can manipulate isolated words and phrases almost infinitely, but context anchors language to its meaning. And language generally — let alone legalese — has little use but to convey meaning.

The major questions doctrine buffers American democracy not against congressional delegation per se, the way the nondelegation doctrine does. Rather, it guards against ambitious bureaucrats who wish to arrogate to themselves Congress’ constitutionally vested authority.

Some Wisdom

Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom is a classic.

In a much quoted passage in his inaugural address, President Kennedy said, "Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country." It is a striking sign of the temper of our times that the controversy about this passage cen- tered on its origin and not on its content. Neither half of the statement expresses a relation between the citizen and his gov- ernment that is worthy of the ideals of free men in a free society. The paternalistic "what your country can do for you" implies that government is the patron, the citizen the ward, a view that is at odds with the free man's belief in his own responsibility for his own destiny. The organismic, "what you can do for your country" implies that government is the master or the deity, the citizen, the servant or the votary. To the free man, the country is the collection of individuals who compose it, not something over and above them. He is proud of a common heritage and loyal to common traditions. But he regards government as a means, an instrumentality, neither a grantor of favors and gifts, nor a master or god to be blindly worshipped and served. He recognizes no national goal except as it is the consensus of the goals that the citizens severally serve. He recognizes no national purpose except as it is the consensus of the purposes for which the citizens severally strive.

The free man will ask neither what his country can do for him nor what he can do for his country. He will ask rather "What can I and my compatriots do through government" to help us discharge our individual responsibilities, to achieve our several goals and purposes, and above all, to protect our freedom?

Some Beauty

Jacob Collier is a nonpareil. His latest:

Some Levity

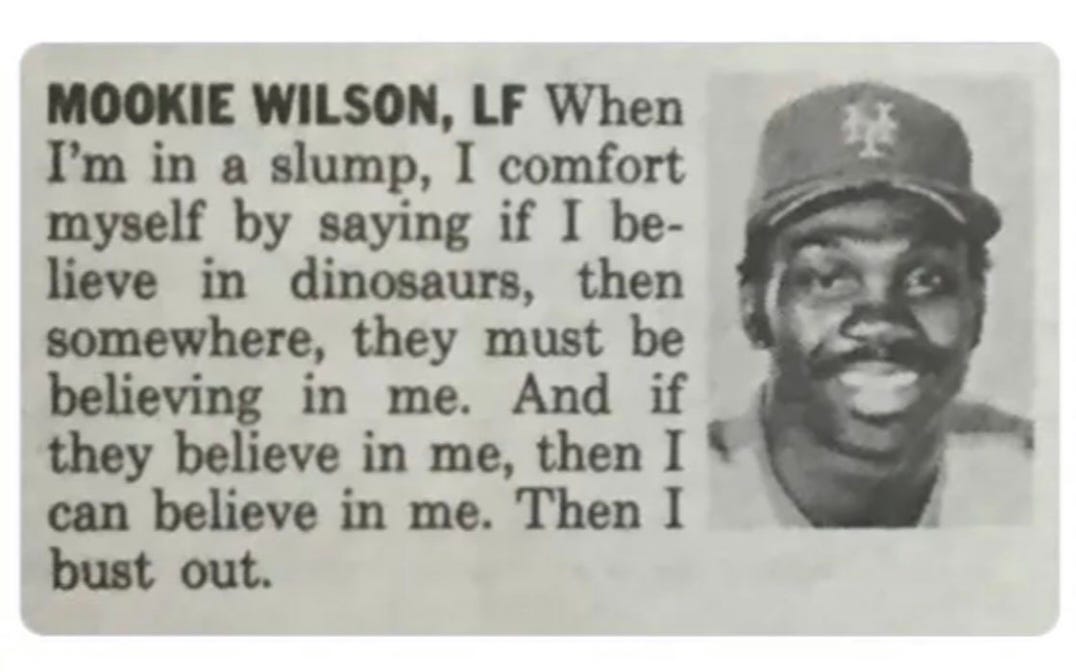

Everybody has his own way to beat a slump.

Sundry Links, &c.

Blog: “The DOJ’s Frivolous Case Is About So Much More than Google”